|

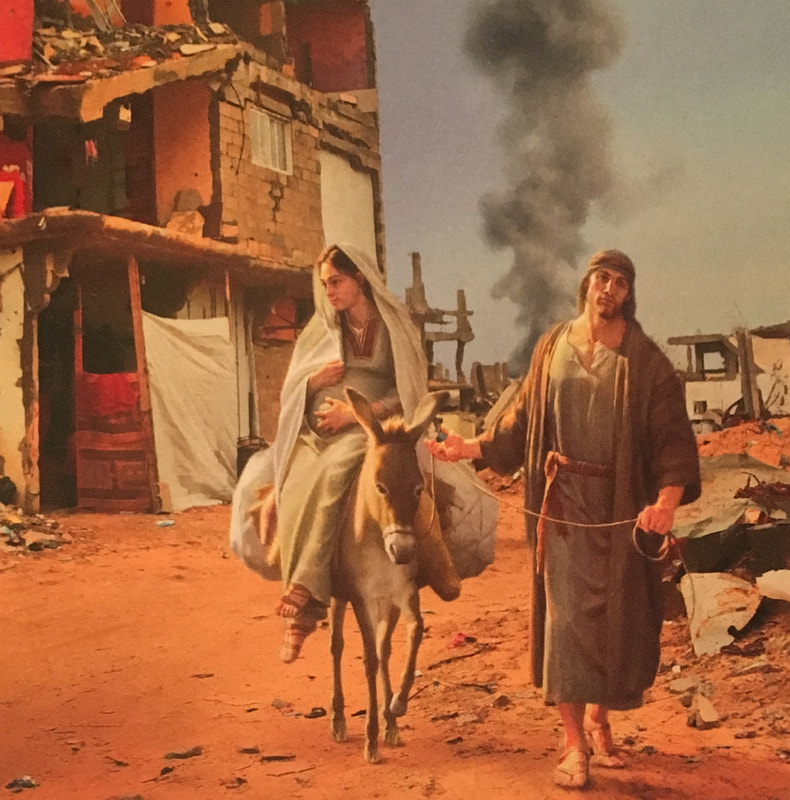

Joseph Brickey(C) 2016 Doctors of the World Charity Christmas Card. Donate £10: text DOCTOR to 70660 Israel’s conflictual relationship with Israeli Arabs, the Palestinian West Bank and Gaza lies at the heart of this year’s prolonged and passionate argument about anti-Semitism in the Labour Party. More precisely it frames Jewish identity in the UK today and shapes the debate whether anti-Zionism is anti-Semitic. This contentious British domestic question relates to the foreign reality of life in the Gaza strip and Southern Israel and to Israel’s role in major violent outbreaks in 2009, 2012, 2014, and during this year’s border fence protests in which 170 demonstrators were killed. Most observers see Israel’s reaction to the danger from Gaza as disproportionate. What then is known about the orchestrator of this threat to Israel’s security, Hamas?

Tareq Baconi in his Hamas Contained, Stanford University Press, 2018, provides insights into Hamas’ history, thinking and strategy. Hamas emerged from the Muslim Brotherhood in 1987 as a radical Islamist movement in competition with the PLO. In the 2006 elections for the Palestinian Legislative Council, Hamas, deemed a terrorist organization by the USA with links to Iran, took 76 out of 132 seats, clearly beating Fatah with its 43 seats. This democratic victory threw an ill-prepared Hamas into government of Gaza (it lost control of the West Bank to Fatah) and triggered a debilitating blockade of the Strip by Israel. The USA under President G.W. Bush gave Israel the opportunity to place Hamas in the post- 9/11 frame by talk of a global war against terrorism. Bush used diplomatic, financial and military means to help Israel isolate the two million Palestinians living in the coastal territory, often described as the largest open-air prison in the world with its 70% youth unemployment, poverty and despair fostering attacks on Israel. Since 2006, Hamas related groups have intermittently attacked southern Israel with rockets, and constructed tunnels to move vital goods in and out, as well as infiltrating fighters and suicide bombers to kill Israeli soldiers and civilians. Over time Israeli military retaliation aimed at curtailing Hamas’ capacity to strike targets in Israel, dubbed “mowing the lawn”, has become increasingly severe. In the course of 51 days, ending in late August 2014, Netanyahu unleashed Operation Protective Edge: aerial attacks on Gaza using F-16s, Apache Helicopters, dropping one ton bombs, followed by a ground assault into Gaza. Tareq Baconi writes that bombs struck housing, schools, hospitals, mosques and power generators, killing 2,200 Palestinians, 1,492 of them civilians and 551 of these children. “Within Gaza, eighteen thousand housing units had been rendered uninhabitable and 108,000 people were left homeless”. During this same period there were sixty-six Israeli combat deaths and six civilians killed. Baconi tells the complex, and evolving, story of Hamas’ rise to power, its struggle with Fatah and the PLO, to its current containment within Gaza, whilst clearly explaining different strands of Palestinian thinking and ideology. He describes Hamas as defining its role, in contrast to Mahmoud Abbas and the Palestinian Authority, as a religiously motivated resistance to “Zionist” settlements inside the territory occupied by Israel after the 1967 war, and until recently, more generally to the wider Israeli occupation since 1948. Against the PLO, the internationally approved negotiator of the Oslo accords, derided by Hamas for achieving nothing, Hamas presents itself as the movement for liberation of the occupied territories. Hamas frames itself as the - last - anticolonial movement comparable to the ANC’s apartheid-era analysis of itself as fighting against Afrikaner “internal colonialism”. In its own eyes and those of many Gaza residents, Hamas is conducting an armed struggle, or asymmetric warfare, for the land and soul of the Palestinian people against an overwhelmingly powerful military enemy, for the right of return of Palestinian refugees. Because of his efforts to explain objectively, Baconi risks being accused of providing Hamas with historical legitimacy. That is clearly not his intention. Nor mine. But Hamas’ interpreting the conflict in a frame of settler colonialism has as much, or as little, sense as the ANC’s old analysis. Both conflicts could be described as resistance movements facing an opponent with a dramatically different level of coercive military power and different history of occupancy of the contested land. The Palestine-Israel conflict has the additional complexity of each side’s ethnic identities and strong religious claims to a divinely mandated terrain. It is not called the Holy Land for nothing. Establishing new States did not work for “Christian nationalism” in South Africa. Baconi finds scant evidence of any ongoing commitment to the Oslo Accords or to peace-making initiatives on either side. Pursuit of a Two State solution has come to nothing. Hamas statements from its internal and external leaders, Ismail Haniyeh and Khaled Meshal, quoted in the book, refer repeatedly to the enemy as “Zionists”. There is no mystery how some of the Labour Left have been accused of anti-Semitism. For them, rather than framing Zionism as one protagonist in a clash of nationalisms, the interpretation motivating the Oslo Accords, Zionism is the powerful last remnant of settler colonialism. This account of the singularity of the conflict is not necessarily anti-Semitic though it easily drifts into anti-Semitism. Most politicized South African young blacks whom I met in the 1980s referred to the “Boers” when they meant the South African security forces. A few were unsurprisingly anti-white. Some Labour Party members surprisingly, disgracefully, have crossed the boundary into anti-Semitism. Baconi charts how Hamas’ strategy and tactics changed as facts on the ground changed, notably in the shifting sands of the Arab Spring in Egypt, and the leadership changes it brought, from Mubarak to Morsi, from Morsi to Sisi. But Hamas has retained its character as a nationalist Islamist movement despite persistent efforts to lump it with Da’esh and Al-Qaida – both of which it actively opposes. And the leadership has tacitly put aside a major ideological prop: the refusal to recognize the state of Israel. Given future flexibility, Hamas could move from ceasefire to meaningful negotiations given the right conditions. Otherwise there are no grounds for optimism. Lives in southern Israel are insecure. Lives in Gaza verge on the insupportable. A humanitarian crisis beckons. Israel’s military power has entrenched rather than defeated resistance. Whether the Israeli government retains any vestigial desire for negotiation, now the USA has de facto finally abandoned its role as peace mediator, remains to be seen. Baconi has written a courageous, if depressing, book. Future peacemakers would do well to read it.

1 Comment

Professor Paul Clough

20/12/2018 22:01:13

Very clear and thoughtful. Well-done. And happy Christmas in the midst of violence - as evoked by the riveting picture/photo at the beginning.

Reply

Leave a Reply. |

Archives

July 2024

Categories |

RSS Feed

RSS Feed